I visit Lofoten, Norway, almost every spring break. This image was taken in 2018. It shows the cameras used by the members of my team. We had seven ALPA cameras and one Cambo.

Why Medium Format?

To put it simply: we want image quality better than the one provided by smaller sensor cameras. It’s true that cameras don’t create artwork. Photographers do. However, in landscape photography, the size of the final presentation has a huge impact on viewer experience. It’s true that many people only view landscape photographs on computer screens or even on tiny phone screens. However, once they see high quality big prints in a gallery, they will immediately understand that it is a completely different experience.

Generally speaking, if all other things are equal, the larger the prints are, the stronger the visual impact will be, at least for "grand landscape" types of work. Of course, this is a general rule and you can always find exceptions. For example, some minimalist landscape photographs, which do not have much details, look elegant inside a small picture frame but often are terrible on a 2-meter print. Large prints, those over 2-3 meters, require image quality only a digitial medium format camera can provide (large format film cameras also work, but let us focus on digital imaging only in this page.)

You need to know if you really need all the megapixels or not. If you only shoot for magazines, for example, then 35mm DSLR cameras are perfectly fine. You will not see a major difference in image quality between a good 35mm camera and a high-end medium format camera, even on double page spreads. These prints are too small to see the advantage of the latter. Some might argue about the existence of a "medium-format look". As a landscape photographer, I don't know if such a thing is real or just an illusion, but I will not argue with anybody on this topic. You can never win a religious war. If you think that there is such a thing, or CCD is better than CMOS, or the Earth is flat, that is totally fine with me.

Medium Format (MF) is used to refer to film formats that are larger than the ubiquitous 35mm (24X36mm) film. Typical medium formats include 645(6x4.5cm), 6x6 (6x6 cm), 6x7, 6x9, 612 (6x12cm), and 617 (6x17cm). Their sizes are much larger than that of 35mm film, but smaller than Large Format (LF) film formats such as 4X5 (inch) and 8x10 (inch), hence the name "medium format".

Digital Medium Format and Its Advantages

In the era of digital photograph, digital MF refers to cameras with a sensor that is larger than that of a 35mm (full-format) DSLR camera. For example, the sensors used by Phase One 3100/4150 are of 54x40mm (digital 645 format), which are 2.5 times larger than the ones in 35mm DSLR cameras. Compared to smaller sensors using the same generation of technology, larger sensors typically bring better resolution, better dynamic range, and better color depth.

There are no commercially available large format digital sensors. The cost of manufacturing sensors increasing exponentially as the size of them increase. 54x40mm sensors, which are already prohibitively expensive for most users, are the biggest on the market. On the other hand, modern digital MF systems offer incredible image quality. The best of them exceed the image quality of 4x5 large format film, and are closing the resolution gap between the digital capture and 8x10 large format film. With the easy stitching capability of a MF tech camera, it is possible to very easily produce a digital image that matches or exceeds the resolution of 8X10 film.

On the other hand, the dynamic range, the reliability, the weather resistance capabilities, and easy of workflow of digital far exceed that of 8X10 film systems. In other words, digital MF completely change the game of high-end photograph by removing most of the severe inherent limitations of large format cameras. For the first time, we can capture a much wider variety of sceneries and images, from starscapes to innovative wide-angle compositions, while still maintaining the exceptionally high image quality that only large format cameras could provide a few years ago.

However, digital MF means much more than just sensor sizes. In real world photography, we are also talking about very different lens qualities, different ways to photograph, and very different workflows and mindsets. In other words, it is pointless to just compare sensor sizes and declare "mine is bigger than yours". We need to look at systems as a whole and compare them.

Why Medium Format Technical Cameras?

For several years I used a Pentax 645Z digital medium format camera, a fine piece of equipment. It sports a 50MP sensor of 44x33mm, about 1.7 times larger than that of a 35mm DSLR camera. The HD DA645 28-45mm lens is sharp. The controls are logically placed, reminding me of the Pentax 67II medium format film camera which I once owned. Later I used a PhaseOne XF camera which comes with an even bigger sensor. There are other similar automatic MF camaras (SLR or Mirrorless) on the market, among them, Fuji GFXs are probably the most popular one.

All of these are good cameras. They are automatic. There is virtually no learning curve. If you know how to operate an 35mm DSLR, you can start shooting with such a camera in minutes. They have autofocus zoom lenses, making them ideal to shoot in situations where timing is important - for example, shooting moving subjects or doing aerial work from a helicopter. The Fuji GFX and the Hasselblad X1D are relatively affordable - not much more expensive than top-of-the-line 35mm systems. While Pentax 645Z and PhaseOne XF are very heavy, the new mirrorless systems are portable. However, such systems are not without limitations. The ones with 50MP 44x33mm sensors do not offer much meaningful image quality improvement over their best 35mm counterparts, although the 100MP version is far superior. Most of such systems lack super-wide-angle lenses, which is probably the biggest hurdle for landscape photography. The Pentax 645Z and PhaseOne XF (two bodies I own) and their lenses, are very heavy. Personally, I think they are probably best used in a studio, not in real-world outdoor environments where one needs to hike long distance over difficult terrain.

-

The biggest limitation with such systems is that they do not allow for technical movements that are available on technical cameras.

There are three types of movements:

- Tilt/Swing:

-

With the forward tilt movement, I can capture the foreground that is very close to the lens, and the mountains at infinite, in a single shot, at f/11. No focus stacking required.

On modern high-pixel-count systems, diffraction limits the smallest aperture one should use. On an IQ 4150, if you want the best image quality, try not use an aperture smaller than f/10-11. The problem is, in landscape photography, we often need the depth-of-field that calls for a smaller aperture (which we should not use). While we can use focus-stacking to solve this problem, it is often easier and faster to use tilt/swing movement to fix most of such problems in the field.

- Vertical Shift (Rise/Fall):

-

This type of vertical distortion (look at the leaning trees and their reflections) is very common in 35mm wide-angle landscape photography. It can be avoided using veritcal shift movements.

This movement is used to avoid perspective distortion when shooting tall trees, mountains, or architecture. You can fix perspective distortion in post, but you lose many pixels in doing so. - Horizontal Shift:

-

Easily creaty perfect panoramas using horizontal shift movements, AND avoid vertical distortion at the same time with vertical shifts. This is the power of technical cameras.

This movement is extremely useful to create distortion-free and parallax-free stitched images. Most of the time we use stitching to create panoramas, but we also use it to get even higher megapixel counts with a normal aspect ratio. While you can rotate the camera and stitch images, the result is very different. - ALPA:

- ALPA offers complete MF body solutions: from the ultra-portable 12 TC/12 STC to heavy-weights 12 MAX and 12 PANO. Many people own more than one of these bodies for different purposes. You can use almost any ALPA lenses on any ALPA body. The engineering and build is absolutely fabulous. ALPA cameras are very expensive. But, you can probably enjoy the legendary precision and durability for the rest of your life. They are not perfect, as there is no such thing as a perfect product.

Most ALPA bodies can shift/rise/fall. To perform tilt, you need to add a tilt-adapter between the lens and body. A few "long-barrel" lenses (explained later), notably the HR 23mm lens, cannot used in this way. Therefore, you cannot tilt the HR 23mm lens. This is my biggest complaint about the otherwise most fantastic camera systems.

ALPA's movements can be both geared (for precision) and slid (for speed), or both (depending on the model). For geared movement, if you disengage the gear, you can slide the digital back or lens very quickly. I like the speed of sliding movement. This is a big advantage when you perform pano-stitching for fast-moving clouds where literally ever second counts.

There is something special about ALPA cameras. They look deceptively simple but are elegant and powerful. They are more than just beautiful and are tools of precision. To quote from ALPA's website, "ALPA is not only a product but an attitude. An attitude of joy, professionalism, and the spirit of discovery." This is not a market slogan or a religion. You appreciate it once you use an ALPA camera for a while. - Cambo's Wide RS Series:

- Cambo's MF tech cameras are popular and capable. The build quality isn’t up to the standard of that of ALPA, but it’s adequate and at a much lower price point. There are two interesting features that I found useful. The first is that many of their lenses feature an integrated tilt and swing mechanism. The second is that the WRS-1600 has a unique feature "to rotate the full camera/lens/back assembly in the tripod mount between landscape and portrait mode within seconds, without removing any part and still keeping the optical center in the same position." (quoted from Cambo website). With an ALPA, you have to unmount the back, rotate it in your hand, and remount it. Every single time I have to rotate my digital back on my ALPA while standing in water or mud, I long for this feature.

- ARCA-SWISS R Series:

- The essence of ALPA designs is "less is more", while ARCA-SWISS tries to present a complete solution. This line consists of RM2D, RM3Di, and RL3D. The quality of ARCA-SWISS products is indisputably high. All three can shift/rise/fall. RM2D does not tilt, while RM3Di and RL3D sport a built-in front-axis tilt mechanism of +/-5 Degrees. As a result, you can tilt the HR 23mm lens. I have many, many friends who use ALPA cameras. I know only two people who use ARCA-SWISS. Both are excellent systems, though. I am not sure about the exact reason why I don't see them more often. I have heard some complaints about the difficulty of mounting lenses and other issues, but they are minor ones. However, if a company does not even have a website in the year 2020, and at the same time there are other competitors on the market that make products as good as theirs, or maybe in certain aspects even better than theirs, shall I dare to say, I am not surprised by the result. Some may argue that ARCA-SWISS C1 and D4 heads are popular among MF photographers. However, this is a complete different story. There are very few competing products in the high-end geared head segment, so ARCA-SWISS essentially enjoy a market monopoly.

- PhaseOne XT:

-

There’s a new kid in town! For years, Phase One has been making digital backs that are used on the bodies of other vendors such as ALPA.

They also make the XF camera, which is a digital MF SLR type, not a technical camera. As I said before, the XF is mostly a studio camera for fashion/product/portrait types of work. Architecture/landscape and other similar genres probably are best left for technical cameras.

Last year (2019), Phase One entered the MF tech camera market with their XT camera, directly competing with ALPA. The camera introduced some nice automatic features which are long overdue in the mostly stalled MF tech camera world, where real innovations are far and between.

XT is made by Cambo (so Phase One is collaborating with Cambo instead of competing with them). XT can shift/rise/fall. The body and the native lenses do not tilt. However you can use Cambo lenses (many of them come with built-in tilt mechanisms) on XT. Of course you lose many new features by using these legacy lenses. I will discuss the XT in detail later.

Technical Cameras

Enter technical cameras, the world of ALPA, Cambo, PhaseOne XT, ARCA-SWISS, and Linhof, etc. Note: the term "technical cameras" was originally referred to almost any cameras with technical movement capabilities, including view cameras. Recently, some people started to reserve the name "technical cameras" specifically to module-designed, rigid-framed modern cameras such as ALPA and Cambo WRS, while using "view cameras" to describe traditional systems with bellows from Linhof, etc. In essence, these rigid-framed cameras are nothing but some simple, interconnected thin metal frames. People often call them "pancake" designs. Typically, there is one frame sliding horizontally and/or vertically inside another metal frame. These are crazy-expensive but smartly designed and highly precise metal boxes! With the exception of PhaseOne XT, all of them are pure mechanical devices, with no electronics or automation whatsoever.

It is always fun to see many different types of medium format technical cameras, particularly in a beautiful location such as in the Dolomites, Italy. Here my group brought eight technical camera systems, among them were ALPA 12STC, ALPA 12MAX, ALPA 12Plus, ALPA 12Pano, and PhaseOne XT.

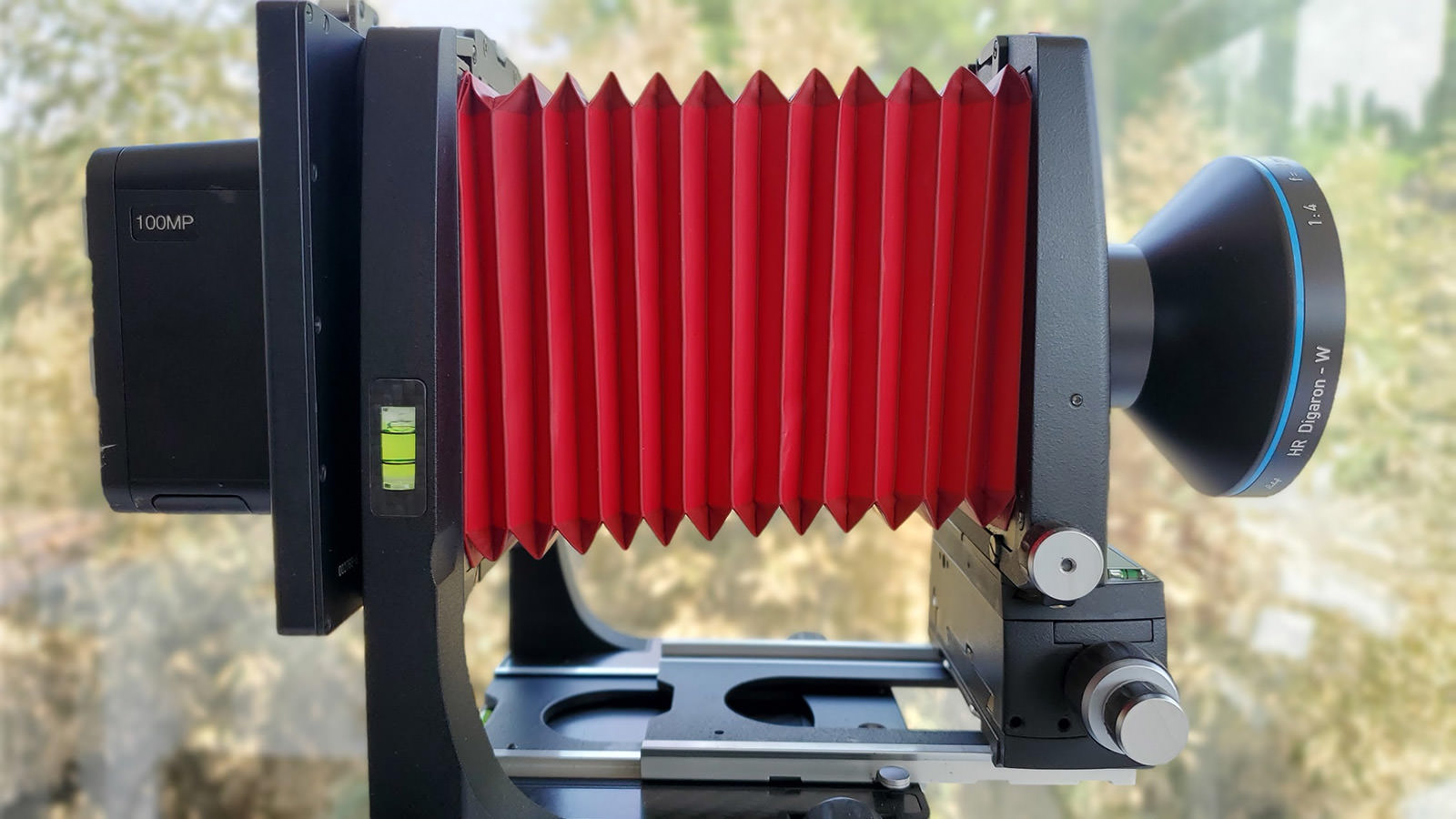

I did not choose Linhof or other cameras with bellows (e.g., Cambo ACTUS DB). One advantage of such systems is that many of them are compact when using long lenses. Since you can freely extend the bellow, you do not need barrels for lenses. These barrels, especially the ones for long lenses, take up a lot of space in my camera bag. Bellows are flexible, so these systems also offer impressive capability of movements. However, the bellows are generally quite fragile and tend to flap in the wind.

Moreover, they are much slower to set up and operate. Also, you need to use the live-view function of the digital back to focus, which is very difficult or even impossible to do in the dark or at night. I saw my friends struggling with setting up then focusing in the dark for 30 minutes or more. The only way they could focus was to use a high-power flashlight to illuminate some foreground, so they could see something on the ground glass or the LCD screen of the digital back. By doing so, they completely ruined everyone else’s long exposures, but they are our friends, so no complaints were filed. Still, with all the troubles they often went home with some out-of-focused images, and I really feel sorry for them. I have also heard that people set up and focus their cameras during the daylight, leave their equipment in place overnight, and come back the next early morning so they could capture the beautiful dawn colors. As a landscape photographer, many of my images were taken under dim-light situations (during dawn/dusk, inside very dark ice caves, or in the middle of night ) in harsh weather conditions. I need a different system. These bellow cameras are probably best for doing architecture photography in cities.

By contrast, with a pancake technical camera, I can take it out of my backpack, mount the lens, turn the focal ring to infinite or the hyperfocal mark (for many Rodenstock lenses, it is 2-3 marks before the infinite), and start shooting in less than one minute. And I often do this in the middle of night.

Linhof Techno Special Edition. What a beautiful piece of artwork! I was seriously contemplating getting one. In the end I knew that this camera was not for me. A friend of mine who mostly shoots architecture eventually acquired this beauty.

Who Are Making Technical Cameras?

-

In most markets, there are basically four MF technical camera systems to choose from:

For landscape photography in the wildness, I chose ALPA for its compactness, its unmatched precision and reliability, rigid design, fast operation, easy setup, and unmatched service and technical support from my dealer. With High Precision Focusing (HPF) rings mounted and calibrated on lenses, one can perform precise focus in total darkness in a matter of seconds. Contrary to popular belief, I have found over and over that it is much easier to shoot starscapes with an ALPA than with a 35mm camera. The movements on these rigid-framed cameras are somewhat limited compared to traditional view cameras with flexible bellows. For example, you can cannot perform tile and swing at the same time. However, for landscape work, it is almost a nonissue because such flexibility is seldom needed.

In the bitter winter of the Canadian Rockies, temperatures often drop to -40C (also -40F). Weather-resistant is paramount. Technical cameras perform well in such conditions. Through the years, for all the people who have shot with me in different parts of the world, only a couple of friends have ever brought a camera with a bellow (for example, a Cambo ACTUS DB) with them. It was hard to work with in many locations such as the infamously windy Patagonia. Everyone else brought their rigid-framed systems, such as all types of ALPA bodies, Cambo WRS, ARCA-SWISS R, and recently the PhaseOne XT.

The Components of Medium Format Technical Cameras

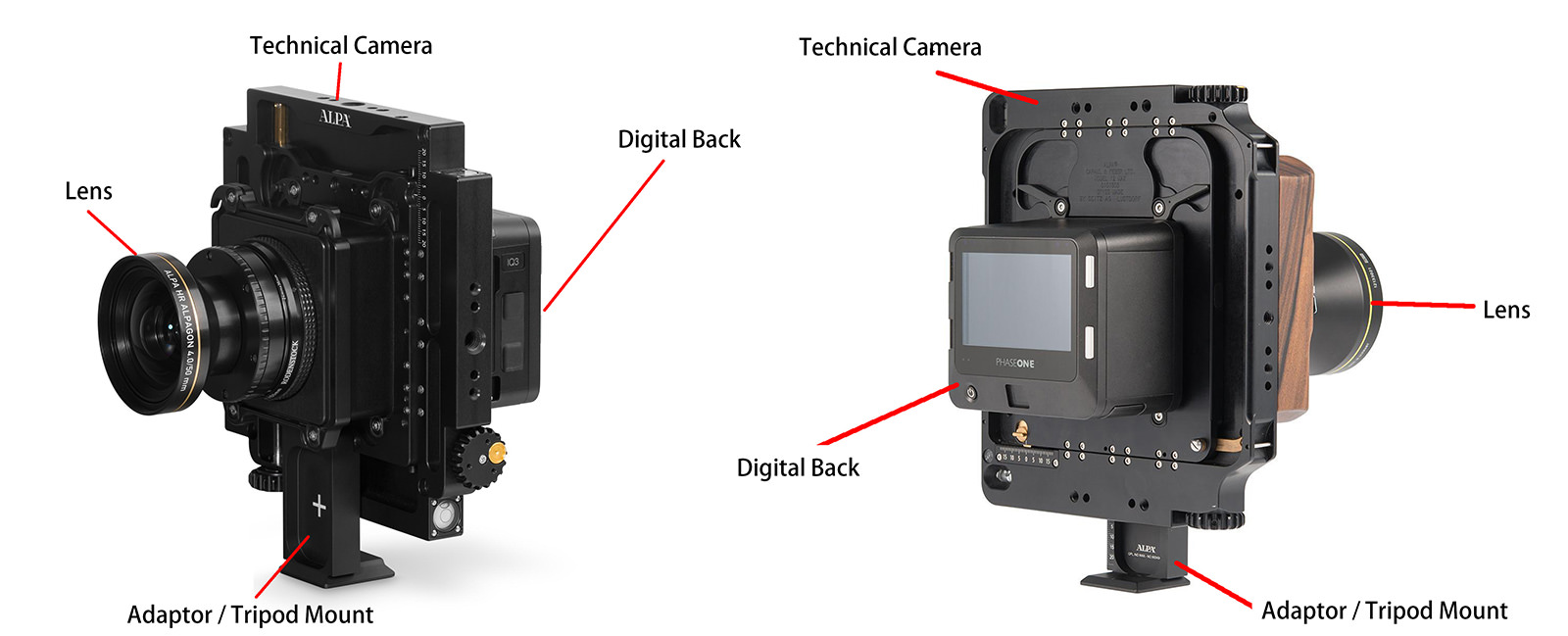

Front and back views of a typical technical camera system. The lenses, the camera body, and the digital back are typically stored separately in the camera bag. They are put together at the location.

Most technical cameras are open systems. The camera itself is just a metal frame connecting the lens and the sensor together. The sensor and the electronics exist in the form of digital backs. With a mounting adapter, you can mount digital backs from different manufacturers on the camera. Phase One makes the best digital backs, although typically you can mount the back from Hasselblad or other brands as well. Some systems even allow you to install another camera (such as a Hasselblad X or a 35mm Sony mirrorless) as the sensor.

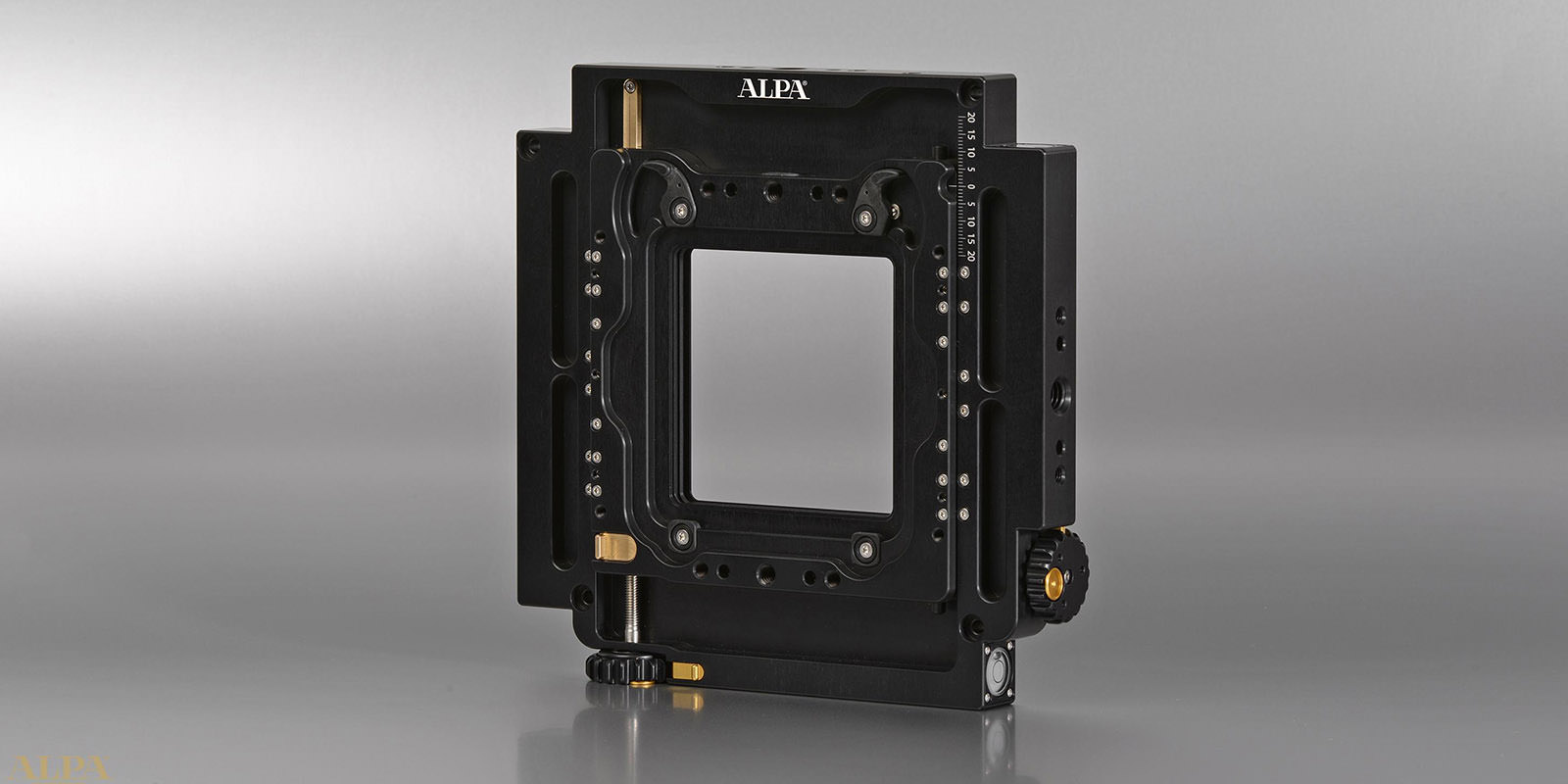

ALPA 12 Plus camera looks deceptively simple. It is just three metal frames - two of them move (rise/fall/shif) inside an outer frame.

As of this writing, the best lenses for technical cameras are made by Rodenstock. With the announcement of the Phase One IQ 4150 digital back that resolved some issues, some users have found that certain Schneider lenses are also an excellent choice. Note that lenses designed for different systems are typically not compatible. So if you have a Rodenstock HR 23 lens with Cambo mount or PhaseOne XT mount, you cannot use it on an ALPA. You’ll have to shell some serious money to buy the ALPA version. Because of such incompatibility issue, switching systems is not an easy decision.

It seems that nobody wants to make an adapter so you can use lenses with different mounts. The market is too small and there is no incentive doing so. You can, however, send the lens to the manufacturer to modify it, for a significant fee (1000-5000 US dollars) of course. Phase One has just designed adapters so their own blue-ring lenses of their XF system, as well as lenses with Cambo mount, can be used on XT. This is welcome news and is understandable, as Cambo makes the XT and blue-ring lenses are their own products. Finally, ALPA and some other vendors have made a Canon EF adapter, so users can use Canon Tilt/Shift lenses on a technical camera.